On my “Light Over Heat” YouTube channel this week, I discuss sociologist Harel Shapira’s opinion essay, “Firearms Taught Me, and America, a Very Dangerous Lesson,” published in the New York Times on 16 May 2023 (gift link here should take you behind the NYT paywall if you haven’t seen the opinion yet).

The title, of course, is provocative and the essay certainly provoked considerable attention on my social media feeds. My gun-skeptic friends had all of their biases about Gun Culture 2.0 confirmed, while my gun-sympathetic friends didn’t recognize themselves in Shapira’s characterization.

As usual, I tried to translate between these two different perspectives, but 140 characters doesn’t allow for much nuance.

So, in addition to 11 minutes of more free-flowing “Light Over Heat” video comments, this blog post presents the points I would like to make more systematically.

TL:DR I have learned very different lessons from firearms classes than Harel Shapira.

[1] I know Harel Shapira

First, I know Harel Shapira personally. In fact, I invited him to present an early version of his research on defensive gun training to my Sociology of Guns course and to the Wake Forest University community back in 2016. His concept of “civilized violence” doesn’t appear in his NYT essay, but it is insightful and I imagine it will appear in his book-length treatment of this, Basic Pistol: Living and Dying by the Gun in America (forthcoming, 2024).

Our paths have since crossed several times, both IRL and in print. I published my analysis of “The Rise of Self-Defense in Gun Advertising: The American Rifleman, 1918-2017″ in a book Shapira co-edited with Jennifer Carlson and Kristen Goss; he published an article on “How Attitudes about Guns Develop over Time” in a professional journal I co-edited with Trent Steidley; and our work has appeared alongside each other in another book, The Lives of Guns.

[2] Shapira is not dishonest

Therefore, I do not think that Shapira is lying or being disingenuous in his NYT essay. I think he is accurately reporting what he saw in his research.

[3] Empirical Limitations

Of course, what he saw is limited by his own data. He notes in the essay that he observed 42 classes and interviewed 52 instructors and 118 students in at least four states (Texas, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Illinois) but “immersed” himself in firearms schools in Texas, where he teaches at the University of Texas in Austin.

This is actually considerably more research than went into other books on defensive gun culture like Jennifer Carlson’s pathbreaking Citizen-Protectors: The Everyday Politics of Guns in an Age of Decline or Angela Stroud’s Good Guys with Guns: The Appeal and Consequences of Concealed Carry (2016).

Having done qualitative research my entire career, I can attest to how much time and effort goes into this doing much observation.

I can also attest to the humility that doing empirically limited qualitative and interpretive social research should bring. Such humility was not on display in Shapira’s opinion essay. Of course, the New York Times would not publish it in that case.

[4] Subjective Limitations

Beyond the empirics, what he saw is also shaped by his personal/cultural orientation to guns and the intellectual frameworks he brought to/developed in his research.

This is not a condemnation of Shapira, but a simple recognition of how social science (and, some would argue, natural science) actually works. As I learned as an undergraduate at UC-Berkeley studying theory under the renowned Marxist sociologist Michael Burawoy, there is no perfect standpoint of objectivity in research (“Punctum Archimedis”).

“There is no well so deep that leaning over it one does not discover at bottom one’s own face.”

-Philosopher Leszek Kolakowski

I actually went off on the New York Times editorial board over eight years ago and what I wrote then applies here as well.

But this does not mean that everything is completely relative and the quest of objectivity should be abandoned. To the contrary, it means we should redouble our efforts to recognize and distance ourselves from our biases. Personal efforts at critical reflection can help, and so can participating in a community of science as individuals with different personal starting points engage in dialogue that can surface their biases.

Of course, if everyone in a scientific community shares the same starting points, then the biases never get surfaced, as seems to happen among public health scholars studying guns and violence.

Incredibly, I wrote that before having read Jonathan Haidt’s The Righteous Mind in which he makes essentially this same point, that “good reasoning [is] an emergent property” of a “community of scientists” characterized by “intellectual and ideological diversity.”

[5] Therefore, Shapira’s Truth is Partial

So, I do not think Shapira is simply wrong in his observations about firearms classes. But his truth is partial, in both senses.

It is incomplete (point #3) and represents a particular perspective (point #4).

[6a] Differences in Observations

There’s nothing wrong with #5 per se. My own research and writing on guns are also partial. Whereas Shapira seems to have focused his attention on lower-level, local, basic gun training courses, I have spent most of my time studying high-level, national gun trainers and courses (though I do know there is at least one very advanced gun school we have in common).

This surely accounts for some of how we may see things differently. Many people I know in Gun Culture 2.0 are critical of poorly-qualified self-defense instructors and poorly taught self-defense courses. John Correia of Active Self Protection, for example.

And as I have written about in a series of posts on this blog (e.g., this one on “What is a ‘professional civilian firearms trainer'”), with the exception of concealed carry instructors in certain states (like North Carolina), “civilian firearms instructor” as an occupation is unregulated by any local, state, or federal agency. In such an environment, anyone can put up a shingle that says “I are a gun trainer,” to quote Ken Campbell, COO of Gunsite Academy, a nationally-recognized gun school I have observed.

So, the likelihood that Shapira observed low-quality but probably common forms of firearms instruction is high. By contrast, I have focused on what in 2018 I called “the frontiers of defensive gun culture,” like John Murphy’s Concealed Carry: Advanced Skills and Tactics course, Alliance Police Training’s Carbine Shoothouse course, Craig Douglas’s Extreme Close Quarters Concepts course, and The Complete Combatant’s Force Readiness course. (There are many others I have not yet had the opportunity to observe.)

I have additionally been exposed to some very deep thinkers on issues of personal defense, like John Correia (“Lessons Learned from Watching 20,000 Gunfights”), John Johnston (“The Work Never Ends”), Dr. Sherman House (“Becoming the Civilian Defender”), and Claude Werner (“Negative Outcomes, Standards, and Gun Culture 3.0”), to name just a few.

My different take on the defensive firearms training (cottage) industry in comparison to Shapira’s can be found in the specific links scattered about this post as well as in my collected posts page on this blog.

[6b] Differences in Interpretation

However, beyond us studying different parts of the gun training industry, there seem to be differences even in how we interpret the same things. For example, Shapira asserts that the classes he observed “trained students to believe that their lives are in constant danger.” The classes I observed also addressed the issue of risk, but the focus was more on the ever-present possibility of danger but the low probability of danger.

As Shapira rightly observes, “It’s not the odds, I heard on numerous occasions; it’s the consequences.” The lesson Shapira learned from this is “that I ought to shoot even when my instincts might tell me otherwise.” In other words, shoot first and ask questions later.

As I have written on this blog, and at greater length in a chapter of my so-far spurned book, low odds/high stakes is part of the gun culture version of Pascal’s Wager. While some people no doubt respond to Pascal’s Wager with religious fanaticism — shoot first and ask questions later — Pascal suggests a more cautious, reasoned approach.

I’ve seen cautious, reasoned approaches discussed incessantly in Gun Culture 2.0. Specifically, how practices of avoidance, awareness, and preparedness — the motto of gun educator Michael Bane’s TV show “The Best Defense” — can lower people’s risk of needing to shoot at all. As the cliche suggests, “The first rule of gunfighting is don’t be there,” or as gun writer Tam Keel puts it, “Can’t lose a fight you’re not in.” Follow gun trainer John Farnam’s “rules of stupid.” Heed trainer Craig Douglas’s admonition to “not let things get shitty” in the first place.

Of course, risk assessment is subject to all sorts of biases (h/t Daniel Kahneman), but Shapira sees his fellow students as worse risk analysts than I see in my wandering around gun culture. In this, he is working within what I have called The Standard Model of Explaining the Irrationality of Defensive Gun Ownership. Insofar as he focuses on hegemonic masculinity and whiteness, he contributes to the argument that something other than objective risk motivates defensive gun ownership.

But back to our different ways of interpreting the same data, using the color codes of personal awareness codified by Jeff Cooper, one of the founders of the civilian defensive gun training industry via Gunsite. Shapira interprets instructors as saying students should constantly be in code orange (specific alert, full attention) or even code red (mental trigger, fight or flight), while I saw instructors suggesting students avoid code white (unaware and unprepared) in public and to be in code yellow (relaxed awareness) instead.

Consider the following scene portrayed by Shapira:

Outside a restaurant in Austin, an instructor saw a disheveled man sitting on the curb and nudged me in the other direction, directing me to pick up the pace. He said he had detected “potential predatory behavior” and wasn’t sure if this man was a panhandler or someone about to stick a gun in our faces.

Harel Shapira, New York Times

For Shapira, this is the kind of avoidance that reflects people being trained “to be suspicious and atomized,” which in turn undermines “the kind of public interactions that make democracy viable.” For me, this is the kind of avoidance that reflects people being aware of their surroundings and taking simple, non-threatening, non-violent actions to protect themselves. It’s the kind of avoidance my sisters (who have never taken a firearms class) use when they walk around San Francisco. It’s the kind of avoidance that my mother (who has never taken a firearms class) uses when she doesn’t answer her front door for people she doesn’t know or is not expecting.

It’s not the only possible response to this situation (see the concluding section below), but it’s also not a democracy-corroding response.

Obviously, there’s more to Shapira’s argument than this particular incident or that specific class teaching. Big picture, Shapira correctly identifies the “primary lessons” of defensive firearms courses as being “if and when to shoot someone on purpose” (emphasis added). Intriguingly, Shapira suggests “this is where the trouble begins.”

Here I suspect, but cannot prove, that Shapira’s view reflects a common sentiment among liberals in the academy studying guns: That the very idea of shooting someone on purpose is offensive. For example, he writes, “Repeatedly the lesson was that I ought to shoot even when my instincts might tell me otherwise.”

Would Shapira’s instincts ever tell him he ought to shoot someone on purpose? Perhaps we will find out in his book.

As for me, my instincts tell me that I don’t ever want to shoot anyone on purpose. Going back to my childhood worship of Dr. Martin Luther King and his ethic of nonviolence, I feel that “violence is rarely the answer,” to quote Tim Larkin. But, he continues, “when it is, it’s the only answer.”

So, my instincts have definitely been shaped by involvement in Gun Culture 2.0, teaching me that violence can be virtuous and to distinguish between the black swan times when violence IS the answer and the normal times when violence IS NOT the answer. This is in contrast not just to Shapira’s sense of things, but to arguments that participation in defensive gun culture is harmful to one’s character.

At the risk of playing armchair psychologist to Shapira’s armchair psychology (to the extent that he is delving into the psychology of gun owners), Shapira’s own psychology may be playing an outsized role in his interpretations.

“Officially,” Shapira writes, “the message is caution.” I couldn’t agree more. But, he suggests, there is a hidden curriculum (my term not his) in gun schools that affects students far more than what is officially taught.

(Hidden curriculum is a concept emerging from the sociology of education that suggests “the implicit, unintended, and frequently unrecognized outcomes of schooling” can be even more influential on students than the formal curriculum. See an excellent application of the concept of “hidden curriculum” applied to campus rape prevention education by Martha McCaughey, who has also written an interesting treatment on the role of guns in relation to physical feminism. But I digress.)

Shapira argues that “relentlessly harping on the dangers that surround us changes the way students assess those risks” in troubling ways. How does he know?

“I experienced it myself.”

Case in point:

On a recent night I saw a driver who didn’t appear to realize that he was going the wrong way on a one-way street. As the other car approached, I began to slow down, roll down my window and stick my hand out in a friendly gesture. Suddenly I worried the other driver might have a gun. How might he respond to someone slowing down a car and waving at him in the middle of the night? Would he shoot? Probably not. But it’s not the odds, I remember telling myself; it’s the consequences.

Harel Shapira, New York Times

This places a great deal of interpretive weight on how Shapira himself understood the hidden curriculum of gun schools. From this (and surely other examples drawn from his research), he concludes: “That’s the great irony of firearms training: In learning how to use a gun for self-defense, something that seems like it might give you confidence and a sense of safety, people end up feeling more afraid than before.”

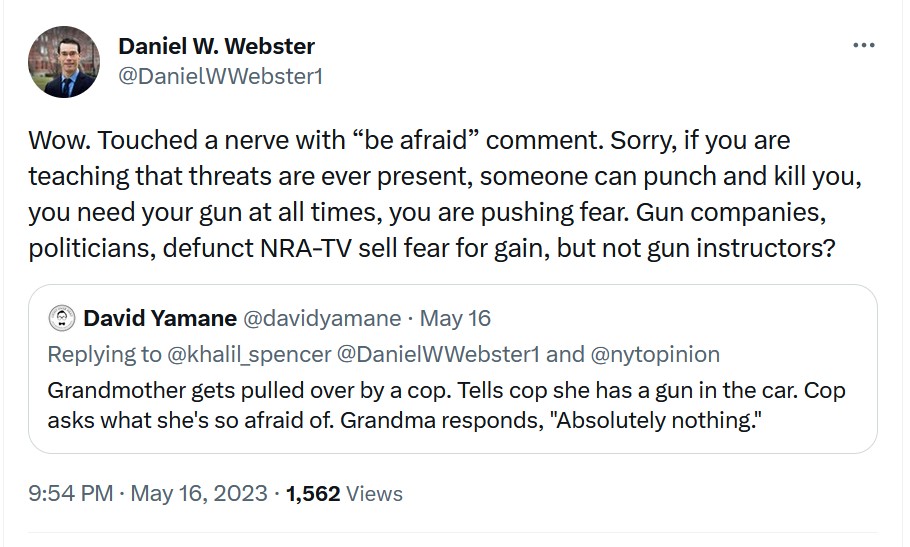

My initial response to reading this was to invoke (on Twitter – my bad) a humorous parable that circulates widely in Gun Culture 2.0: Grandmother gets pulled over by a cop. Tells cop she has a gun in the car. Cop asks what she’s so afraid of. Grandma responds, “Absolutely nothing.”

Although I thought this comment was funnier than gun violence prevention luminary Daniel Webster did (see above), there is truth underlying this quip: Scholars for years have struggled to establish a clear and consistent empirical connection between owning guns and being fearful. Over 9 years ago I wrote about a paper presented at the American Society of Criminology in 2013 that found fear of crime was higher among those who did NOT own a gun.

A more recent study using a broader dataset concluded:

people who own guns tend to report lower levels of phobias and victimization fears than people who do not own guns. This general pattern is observed across multiple indicators of fear (e.g., of animals, heights, zombies, and muggings), multiple outcome specifications (continuous and count), and with adjustments for age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, household income, marital status, the presence of children, religious identity, religiosity, religious attendance, political orientation, region of residence, and urban residence.

Benjamin Dowd-Arrow, Terrence Hill, and Amy Burdette, “Gun Ownership and Fear” (2019)

Of course, this does not systematically compare fear in relation to taking defensive gun training classes, but in my decade-plus of fieldwork on Gun Culture 2.0, I have not seen a systemic connection between these classes and excessive fear.

The lack of a systemic connection either between gun ownership/fear or gun training/fear may help explain why cases like the recent Kansas City porch and upstate New York driveway shootings grab our attention. It’s not their frequency but their rarity (human bites dog, not dog bites human). Of the millions of people who have taken thousands of training courses like Shapira observed — courses which allegedly “prepared [students] to shoot without hesitation and avoid legal consequences” — why are there so few bad shoots?

Considering Shapira’s psychological disposition in relation to his empirical conclusions, the study of “Gun Ownership and Fear” quoted above is potentially helpful. “[P]eople who own guns tend to report lower levels of phobias and victimization fears than people who do not own guns . . . across multiple indicators of fear.” One reason people do not own guns — and react negatively to their use (e.g., having to shoot someone on purpose) — is that they are afraid of guns, just as they are afraid of lots of things in the world (animals, heights, zombies).

This can be interpreted social psychologically, as Jonathan Haidt would, or socio-culturally, as scholars associated with the “cultural cognition” perspective like Dan Kahan would. From the cultural cognition perspective, our worldviews shape our sense of what risks are real and what their potential consequences are. Egalitarians and communitarians, as sociologists tend to be, rate the risk of guns to be high and so favor their control. These assessments are prior to facts, and trump them.

The missing empirical link in Shapira’s argument is especially crucial because of the dire consequences he sees following from firearms class-inspired fear.

[7] The Guns Erode Democracy Master Narrative

As noted in point #4, when all of the partial empirical analyses of a topic come from the same partial perspective, you get a partial master narrative. Shapira’s particular narrative is that gun classes “instill the kind of fear that has a corrosive effect on all interactions — and beyond that, on the fabric of our democracy.”

This is a take on what I have just recently taken to calling the master narrative of democracy destroying right-wing gun politics. I see the narrative (more or less) in the work of Ryan Busse, Matthew Lacombe, Robert Spitzer, Patrick Blanchfield, Andrew McKevitt, and Jennifer Carlson — all of whom have recently published or will soon publish books on guns in America.

And this narrative sells. Big time. As reported in Publishers Marketplace, Pantheon acquired Shapira’s Basic Pistol: Living and Dying by the Gun in America in “a major deal.” This means an advance of more than $500,000 was paid for the book. This is a huge advance for an academic author and means the publisher thinks they can sell a shit-ton of Shapira’s book.

This contrasts sharply and, to be honest, painfully with my experience of 30+ publishers passing on the opportunity to publish my less inflammatory take on gun culture in America.

[8] A Different Mirror

But what if we look at guns, gun training, and gun culture through what the legendary UC-Berkeley historian Ron Takaki (and fellow Japanese-American FWIW) called “a different mirror”? Could this sort of diversity of ideas help us to understand these important phenomena better?

Because, in fact, firearms classes taught me very different lessons than Harel Shapira learned in his study.

From Brian Hill of The Complete Combatant and many others, I learned the value of having a diverse skill set — including pistolcraft, knife skills, martial arts, pepper spray, flashlights, phones, basic medical, and even the defensive value of “Run Fu.” These skills give people the power of choice, including the choice to fully and actively participate in social interactions in public. This, not coincidentally, is how those immersed in Gun Culture 2.0 that I have studied generally live their lives.

From Craig Douglas and others, I learned the power of “social literacy” in navigating public space. As we live our lives in society, we ought not scream at strangers to “get the fuck away!” or draw down on people just because they approach us. Sometimes people need help. They lose their kids or their way, they need medical help or a hand. Being aware of who is around us and being able to recognize pre-assault cues (that Douglas also teaches) can help us determine whether we want to engage an unknown contact and dictate the terms of that engagement in socially literate ways.

For me, the most important part of having social literacy is that it allows us not to treat public space as a battlefield to be negotiated but as a place to be enjoyed. As Douglas put it, “Sometimes you just want to go enjoy a museum without having to worry about whether you have a gun or not.”

After he taught in my Sociology of Guns class at Wake Forest, Douglas and I enjoyed dinner together at the Katharine Brasserie in the former R.J. Reynolds Tobacco headquarters, a beautiful old art deco building in downtown Winston-Salem. From there we walked to Bailey Park, an urban greenspace where I showed him the conversion of old Reynolds warehouses into a high-tech innovation district. We ended up meeting my wife Sandy at Fair Witness Fancy Drinks, a craft cocktail bar nearby. We shared a few drinks and a lot of laughs. And we didn’t have to yell at, eye gouge, punch, stab, or shoot anyone. It was a good day.

Thanks for reading beyond the headline. If you appreciate this or some of the other 900+ posts on this blog, please consider supporting my research and writing on American gun culture by liking and sharing my work.

Thank you for writing this. Will link.

LikeLike

David, are you going to write a response to Shapira’s piece and send it to the Times?

I pretty much agree with what you wrote here. I don’t know what kind of trainers Shapira observed but suspect there are, as Mike Weisser also says, a wide span of competence and attitude as there is no national standard one has to certify to in order to hang out a shingle. New Mexico concealed carry instructors, by the way, have to teach to the state curriculum requirements, which stress conflict avoidance and conflict resolution. That great fifteen minute video by Massad Ayoob describing when lethal force is justified (using that three legged stool of ability, opportunity, and jeopardy) also comes to mind. My own instructor describes WYOR on his web site but I don’t recall hearing him say one should be in perpetual Orange. Seems to me a recipe for a nervous breakdown. Being in Condition White in public could lead to being victimized, just as not maintaining situational awareness, which is what WYOR boils down to, can lead to being victimized in traffic. As a League of American Bicyclists certified instructor, I teach situational awareness, as does the Motorcycle Safety Foundation. It is the bike and motorcycle version of WYOR. When on two wheels (or even four) one should be aware of one’s environment and be scanning for potential problems. Had I been doing that the day I was flying over the hood of a car while bicycling to campus, I could have saved myself a trip to the hospital. Instead, it was a week before my Ph.D. qualifying exam and my mind and attention was, to put it mildly, elsewhere.

I had read Shapira’s piece after it came out and wondered how much was interpretation vs. observation. Seems a response is in order.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Shapira seemed bemused that risk assessment is a product of {chance of occurrence} x {severity of consequence}. My clients very rarely fall of a horse, and only about 15% of horseback riding injuries are to the head. But head injuries can cause serious & permanent damage. So all my clients are required to wear helmets.

I bet Shapira always buckles his seatbelt. So why is he shocked that some of us always carry?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good point about risk assessment. I did a lot of that thinking when I worked in a high hazard facility. That old risk assessment matrix comes to mind. An event with a severe outcome but with a credible chance of occurrence usually gets painted in red or orange, signifying meaningful precautions. Which is why I always wear a bicycle or motorcycle helmet. Knock on wood, I have yet to use my motorcycle helmet for its intended purpose but back in 1986, used my bicycle helmet for its purpose when hitting a patch of ice on a bicycle ride and sliding into a rut on the road that had me doing an ass over handlebars trick. And in regards to guns, helmets, or fire extinguishers, to paraphrase Pascal’s wager, it is better to have it and not need it then need it and not have it. And of course, know how to use it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Khal – thanks for mentioning the video by Mas Ayoob, it’s a good one. While AOJ is a very useful concept to internalize, it by itself does not necessarily justify the use of deadly force. The party facing the threat must also not be the instigator of the conflict, the defensive force used must not be excessive, and both the defender and objective third parties must believe that the defender’s action were reasonable given what he/she knew at the time and the totality of the circumstances.

LikeLike

David, these on-point comments are another big reason you need to stay the course in your work. Rational, well reasoned and counter to what most academics express regarding gun culture and the participants in it. Shapira certainly sounds like he interpreted his experiences in such a way that he confirmed his own biases. And if you are only able to confirm your existing biases, I don’t care how many courses you take or other experiences you have, you’ll not get an objective view of that culture. And I like your quip about the grandmother!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you raised the question of whether Shapira even recognizes the right to use force in self defense. The unspoken assumption among many gun control activists is, ‘there is none.’ (Despite it being black letter law in all 50 states.)

Shapira’s inability to take action, when a loved one was receiving a simulated beating over the head, is revealing. I’d encourage him to reflect on that, what it says about his own worldview, and how that worldview might skew his interpretation of firearms training curricula. Cuz I have to ask — what the hell is wrong with you, Harel?

LikeLike

To be honest, as a psychologist, it would take me a long time to adequately respond to his opinion. It highlights the pitfalls of participant observation as a means of investigating a culture. I’ll take your word for his honesty – but it is clear he went into this with biases and expectations. I’ll be charitable and call them “unconscious.” It is a fine example of confirmation bias; it is clear that these “implicit” biases played a critical part in his perception of the training and interpretation of its meaning and effects. Reminds me of the journalist who said he was “traumatized” by firing an AR. I would say he is engaging in projection.

As you note, it is sad that this is the story that many, including the media and publishers, want to tell. Hence it also offers them confirmation of their biases. I wonder does he – given he is in Texas – and many people with this opinion – realize how often they are standing next to someone who is armed and yet, somehow, they never know?

We incessantly hear about threats from all of our news sources with nightly reports of muggins, shooting, rapes, assaults and so on, yet when people act in ways to become aware of and prepared for such threats, that is somehow dysfunctional. I’ve mentioned before that I teach a seminar on veterans and military culture. In it, I talk about Military Sexual Trauma and about how people can protect themselves. Of course, the response is often “Telling people how to avoid this is saying it’s their fault. You are blaming the victim.” Some think that saying “Bad people should not do bad things” is a magical incantation and, if we demand it, nothing bad will ever happen again. I would echo William Aprill’s notion that “They are not like you” – and they are out there. Closing one’s eyes to it will not change that – armed or not.

Effective communication relies on shared information networks, such that certain words have shared associates which make their meaning (and valence) clear between sender and receiver. I would suggest that his lack of acculturation into the culture and its meanings, along with his own degree of bias, underlies his interpretations. He “knows” it is bad. Unfortunately, there are many people out there just waiting for him to confirm their biases as well.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Well said, Jack – thanks!

LikeLike

> He “knows” it is bad. Unfortunately, there are many people out there just waiting for him to confirm their biases as well.

This is pretty much the social disease of the 21st century – the steady fragmentation of competing, mutually-exclusive realities. Crossing this divide requires that one sets aside so many entrenched Us-vs-Them narratives and speaks to someone on the other side willing to do the same. Unfortunately we’re willing to give Us a pass as being complex and nuanced while They are simplistic, duplicitous, and ultimately Bad People™ whose grievances are illegitimate.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Can’t say I disagree with the diagnosis here. Alas.

LikeLike

I agree with Tom and Jack. This seems like it a case of confirmation bias. I have no doubt that if you wander around a gun class of any size, you will run into someone who expresses the “shoot first” or “better tried by 12 than carried by 6” mindset. Whether or not they are a “bad shoot” waiting to happen is problematic and statistics suggest is rare..

LikeLike

This may be the first time I’ve sense some extra passion in i to our writing, David, while still holding to Light Over Heat. I liked it. Well done.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Have to admit I am a bit worked up right now!

LikeLike

“To be civilized is to restrain the ability to commit mayhem. To be incapable of committing mayhem is not the mark of the civilized, merely the domesticated.”

–Trefor Thomas

For the vast majority of Americans becoming a victim of violent crime is a small risk. To many people, to prepare for a risk is to admit that such risk exists. Same reason so many people don’t have wills or medical powers of attorney. It’s much more emotionally comforting for them to pretend that there is no risk of being victimized, dying, or involved in a traumatic accident, than to face the fact of those risks, no matter how small, and prepare for them.

I have smoke alarms and fire extinguishers in my home. I keep a fire extinguisher in each of my vehicles. This does not mean I’m in fear of and constantly on the alert for fire. I’ve needed to use a fire extinguisher once in my life when my son failed to read the section of the instructions for heating pre-popped popcorn in the oven that said “remove from bag before heating”. My having a fire extinguisher handy reduced what could have been a devastating, life-altering event into an inconvenience.

I view firearms in pretty much the same light as a fire extinguisher, a will, a medical power of attorney, or a first aid kit: I’d rather have one and not need it than need one and not have it.

LikeLike

Appreciate these points and reflections. I have called defensive gun ownership as a version of Pascal’s Wager, which you highlight here with fire extinguishers, POAs, first aid kits. Thanks. https://gunculture2point0.wordpress.com/2021/03/15/pascals-wager-self-defense-and-gun-ownership/

LikeLike

I found this very refreshing: recognizing that people arrive at different views of the same event observations based on the experience they bring with them. It’s not that “they” (or we) or “idiots, but often we don’t learn from the viewpoints of others or from fresh observation with a mind open to new interpretations.

In the last few paragraphs I thought of an analogy to “… go enjoy a museum without having to worry about whether you have a gun or not.” I used to attend conferences in California and Florida driving a 20-year-old Honda Civic with about 400,000 miles wear. People were credulous and often asked if I was concerned that it might not make the trip. I would reply, “No. I can resourcefully repair most things likely to happen (because I am prepared and trained), and in the event of catastrophic failure I am prepared (and capable) to replace it.

I don’t go “looking for a flat tire” any more than I go “looking for a personal interaction conflict. I go about my day armed, and often forget the weapon is even there ~ but I know it’s there as a tool if it becomes a necessary tool. Because I am vigilant, I can avoid a *potential* bad situation. Because I am resourceful and prepared, I have choices of how to defuse, de-escalate, or mitigate a bad situation. And if it gets beyond *that point*, then I am also prepared when that “is the only answer.”

LikeLike

[…] Me, and America, a Very Dangerous Lesson”) from May 2023. I wrote extensively about his ideas here back then, discussed it on “Light Over Heat,” and cover some of that same ground in the […]

LikeLike

[…] is an opinion. Metzl could have cited another New York Times opinion by sociologist Harel Shapira that I have commented on extensively (and addressed also in my book). Whether it will be empirically established in the book remains to […]

LikeLike

[…] Me, and America, a Very Dangerous Lesson”) from May 2023. I wrote extensively about his ideas here back then, discussed it on “Light Over Heat,” and cover some of that same ground in the […]

LikeLike

[…] and America, a Very Dangerous Lesson”) from May 2023. I wrote extensively about his ideas here back then, discussed it on “Light Over Heat,” and cover some of that same ground in the […]

LikeLike

[…] and America, a Very Dangerous Lesson”) from May 2023. I wrote extensively about his ideas here back then, discussed it on “Light Over Heat,” and cover some of that same ground in the […]

LikeLike